It’s been two months since the Chibi Tarot Kickstarter was funded, but for me it’s still not entirely real. I don’t think that’s simply because the cards aren’t in my hand. There’s enough art and momentum at this point that the project is very real. I think that’s because I have a hard time taking credit for my work without external validation. It doesn’t feel like it’s mine, despite all the hard work that I’m putting into it. It doesn’t resonate with me, despite knowing that if someone else was doing this deck I’d be super-stoked for it. This is a personal difficulty I have, a piece of the Work that the Chibi Tarot is a big part of. It’s summed up nicely by an old joke Woody Allen joke that he’d never be a member of a club that would have him, and that’s incredibly true for me.

It’s been two months since the Chibi Tarot Kickstarter was funded, but for me it’s still not entirely real. I don’t think that’s simply because the cards aren’t in my hand. There’s enough art and momentum at this point that the project is very real. I think that’s because I have a hard time taking credit for my work without external validation. It doesn’t feel like it’s mine, despite all the hard work that I’m putting into it. It doesn’t resonate with me, despite knowing that if someone else was doing this deck I’d be super-stoked for it. This is a personal difficulty I have, a piece of the Work that the Chibi Tarot is a big part of. It’s summed up nicely by an old joke Woody Allen joke that he’d never be a member of a club that would have him, and that’s incredibly true for me.

That there’s still a doggedly persistent part of me that’s in love only with the things I can’t have. When it turns out that being an artist is more about keeping at it than it is about transcendent moments with the divine, a bit of the sheen wears away, and since the Kickstarter ended I think I’m still sitting with that. I want the thrill of divine validation: the hand of god descending from heaven to mark me out from the masses. And that’s what I was hoping the Kickstarter would be: god’s message that this project is destined to succeed.

I know, listening to myself, how foolish that sounds. It’s silly to believe that could/would/will happen, but that didn’t stop me from wanting it, even without knowing that I wanted it. That’s the unconscious expectation that I went into the Kickstarter with. Not that it would succeed without work, I busted my ass the entire month (though in two very different ways) to make it happen, but that it would succeed virally; that as I began to put the word out, the world would catch fire with an idea whose time had come, and when that didn’t happen I got very depressed.

I didn’t go into the Kickstarter thinking I was going to fail. Armed with hard work and a great idea that was becoming a great product, a world overflowing with geeky consumers, and being well connected to both pagan and artistic communities, I couldn’t see how I could fail to find an audience. But the audiences I thought I had access to and feeling for turned out to be almost completely uninterested in the product I presented. Where I thought I’d found a nice geeky niche ripe for exploitation, I instead found a small row much in need of hoeing, and I wasn’t expecting that.

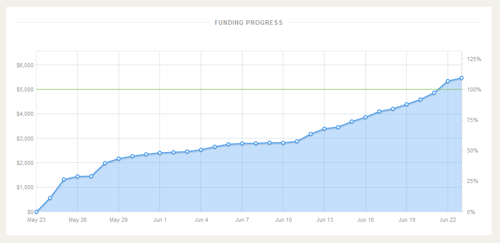

As donations to the Kickstarter flat-lined near the end of the second week of the campaign, I found myself at a loss; I’d expected this to be a commercial success, and when it wasn’t I didn’t know what to do, except be depressed, morose and mope around trying to come to terms with impending doom. It was not a great feeling. I didn’t know what to do next, I felt I’d reached the end of my rope and had no tools left in the bag, to mix a lot of metaphors. I felt I’d already irritated all of my close friends and family to the point of snapping (which wasn’t true at all) with my constant posting, updating and inquiring; submitting the project to blogs wasn’t getting a good return at all (about 1 in 10 got back to me about promoting the project); I’d had no strong inqueries from any one group, and so I felt really had nowhere left to turn to drum up interest. I just had to watch the last 11 days tick past as I stagnated across the finish line.

Like I said, it was a dark time.

Then, during meditation one evening near the end of the second week, I’d finally generated enough distance to see my own assumptions for what they were and realize that I’d unconsciously assumed that the Kickstarter to be commercially successful; that I’d expected others to do the heavy lifting of promotion and the hardest part for me would be developing stretch goals as the cash rolled in. When I finally articulated this previously hidden expectation I’d had, I also realized that there was another method to getting across the finish line successfully. Instead of depending on the commercial model to deliver me, I could instead use the non-profit, grass roots method of fund raising: The personal ask.

In order to do this, though, I had to risk even more in my personal relationships by being direct about asking for money and for help from close friends and family. This was incredibly difficult for me. I already felt like a burden to those around me, a pest whose pet project was clearly not worth funding (if it was, it would already have been funded, and I wouldn’t have had to ask for help or money, obviously) and that I was just too stupid to realize it. In order to risk that kind of disappointment I had to ask myself one question: did I really want to do this?

You might think that the answer to this question is implicit in the art work and the Kickstarter, but for me it wasn’t. There are a variety of ways to develop and promote a project like this, and the self-promotion, self-publishing crowd sourced model developed through Kickstarter is just one of myriad ways I could have gone with it, but as a perfectionist control freak, this method greatly appealed to me. And I could have stopped there, deciding that the Kickstarter was just a failed litmus test, and that there truly was no market for my product, so why keep going?

So, I asked myself, sitting in my dark basement on my meditation cushion: Do I want to do this? The answer I came to was yes. Yes, I do want to do it. The risk was worth the reward.

So I stood up and quickly made a list of 20 of my closest friends and family and I wrote two form letters that I could personalize individually. The first letter went out to folks who’d already given to the campaign and asked them to reach out to five people they knew who were either mutual acquaintances or who they thought would be interested in the project, and ask them personally to give money to the Kickstarter. The second letter went out to folks who hadn’t given, asked them directly to give me money (an incredibly difficult thing for me to do. It’s one thing to ask strangers to buy candy bars to support little league, and another thing entirely to ask friends and family for cash for my personal project), as well as ask five of their friends to give as well. With great trepidation I sent the very first letter to my brother, who I felt was the safest person I could ask since I thought it highly unlikely he’d disown me over it. After the first five letters they got less difficult, but I won’t say it was ever an easy thing for me to do.

Being able to change my approach, pivoting, saved the campaign. I was able to get more support from casual acquaintances through my own personal asks and the personal asks of my close friends than I was able to do through more traditional promotional methods. Not one of the people I emailed disowned me or even complained about the letters, but many of the folks did give, and their friends also gave, and that infusion was crucial to my success, getting 109% funded.

However, because of my own faulty emotional wiring, that success still felt very hollow. Ironically, it was all the hard work that I did to succeed that was proof of my failure. If I was divinely blessed, as I’d hoped to be, none of that would have been necessary. Clearly there’s still a part of me that’s having a hard time letting go of that desire for divine love/attention/validation for this project (for my life, really). Even as I am transitioning from believing that god will help those he’s chosen, to believing that the gods help those who help themselves, the emotional perspective I still experience the Kickstarter from is still one of disappointment. It’s maddening to have achieved something so important, so improbable and still be unable to use it as an emotional touchstone for success and confidence. Instead it remains a reminder that I’m not loved by god the way that I want to be, even if that type of love is unhealthy and I know it. The only way to move beyond that is to reteach myself about how to achieve god’s love (if it’s something we can even achieve, perhaps I even need to take a step back away from the entire concept…), and to learn how to love myself kindly and compassionately. These are wonderful words, and I strive to embody their concepts, but their reality still seems a long way off.